Cooperatives are often formed to benefit a community. But are they really more sustainable than other businesses in practice?

Co-ops, often formed to benefit a community, have grown into major forces globally, collectively earning trillions of dollars in revenue. Image: Carrie Osgood/CLO Communications

If you still think cooperative groups are limited to small grocery stories in hippie towns, think again. Co-ops have become major forces in the banking, insurance and retail industries. Revenues from the 300 largest co-ops total more than $2tn worldwide, and co-ops employ more than 100 million people around the globe according to the International Co-operative Alliance (ICA).

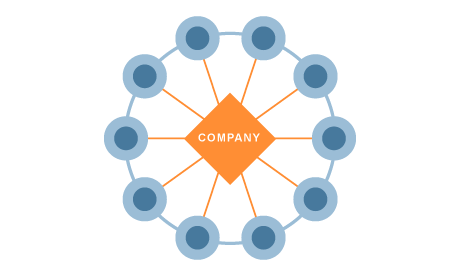

And while corporations have received most of the attention for sustainability efforts in recent years, advocates claim that co-ops are inherently more sustainable. The argument goes that the co-op structure, in which workers or members own the business equally, makes them more democratic than corporations, and therefore more community-oriented. In addition, almost all coops are initially founded to address some sort of societal ill, making them predisposed to tackle issues beyond the scope of traditional business.

"Co-op owners are making decisions every day that balance their livelihoods with the impact in the community," says Charles Gould, director-general of the ICA. "From that, perspective, we believe the model is best aligned with the objectives of sustainability."

For-profit cooperatives, such as REI, the Co-operative Group and Organic Valley, have garnered increasing attention for sustainability mandates that emphasise community engagement, as well as environmental stewardship. Beyond reducing inputs of water and energy and outputs of waste and greenhouse gas emissions, these co-ops are looking to do nothing less than redefine the role of business in society.

They're also helping to change the very definition of sustainability. Few co-ops seem to focus their sustainability efforts on eco-efficiency improvements that have a rapid, measurable impact on the bottom line. Instead, social and community impact tends to play the star role. Depending on the organisation, enhancing sustainability can include community engagement, environmental stewardship, institutional resilience and even employee happiness.

"The co-ops that have become really interesting in the sustainability space are the ones that understand that taking care of their community is a 360-degree task, says Mark Lee, executive director of the consulting firm SustainAbility, based in Berkeley. "The organsations still serve their original [profit-driven] charters, but understand that sustainability writ large is a full package of environmental, social and economic initiatives."

"The co-ops that have become really interesting in the sustainability space are the ones that understand that taking care of their community is a 360-degree task, says Mark Lee, executive director of the consulting firm SustainAbility, based in Berkeley. "The organsations still serve their original [profit-driven] charters, but understand that sustainability writ large is a full package of environmental, social and economic initiatives."

Hiccups in the theory

But as the recent problems at the Co-operative Group demonstrate , co-ops also face their share of challenges. The bank is facing government investigations into its financial struggles – after unsuccessfully trying to buy more than 600 branches from Lloyds Banking Group this year, it's now trying to raise £1.5bn to avoid bankruptcy – and the allegations that its former chairman, Paul Flowers, bought illegal drugs and viewed "inappropriate" content on his work computer.

The shock of these failures happening at the "ethical" bank, as the group marketed itself, is bound to raise questions about whether co-ops are truly sustainable . Adding fuel to the fire is the news, earlier this month, that Spanish appliance company Fagor – part of the world's largest federation of worker co-ops, Mondragon – is headed for collapse .

Seemingly, one of the biggest challenges for co-ops may also be its key advantage: its flat ownership structure. A lack of hierarchy can sometimes, it appears, mean a lack of checks and balances when it comes to selecting leadership and managing governance.

The democratic structure can also, in practice, come with a lack of expertise. Co-ops tend to appoint board members from the community who are less expert than management, Lee says. The Co-operative Group's board of directors, financial regulators noted last year, included a plasterer, a nurse and horticulturalist.

When it coms to corporate sustainability, board members - along with workers or members - also are unlikely to be sustainability experts, meaning a significant amount of research and education might be needed before a plan can be created or a decision made.

In addition, the flat co-op structure means many different opinions, so getting a majority to agree on an aggressive or comprehensive sustainability initiative – for example – or even a definition can be difficult. Getting everyone in a co-op to agree is next to impossible, says Kate Schachter, a driver and mechanic for Wisconsin taxi co-op Union Cab.

And, while some co-ops have the resources and scale of corporations, most remain small, which also limits the scope of what they can do on their own.

Then there's the challenge of proving results. Because co-ops define and interpret sustainability in so many different ways – and because the majority of co-ops are highly local – collecting quantifiable results and independent statistics is no easy feat, Gould says.

Case study: Union Cab

Still, plenty of co-ops have managed to overcome all these obstacles. Take Union Cab, a co-op of 240 full and part-time employees that has been highly proactive in defining and implementing a sustainability program.

In 2009, Union Cab's employee-owners decided to add respect for the environment to the company's mission statement. Within months, Union Cab formed a green team of volunteer employees to figure how best to best act on this mission statement.

"We kind of floundered for a while trying to figure out what we were supposed to do and how we were going to approach it," says Schachter, a member of the green team who has worked for Union Cab on and off since 1980.

A few months later, the green team had settled on its sustainability criteria. It decided that any sustainability measure should reduce the co-op's carbon footprint, reduce energy costs, and increase the environmental awareness and wellbeing of its employees.

Its first initiative was a "no idling" policy for cab drivers. "Every couple of hours a canned message appears on the dispatchers screen to read 'Turn off your vehicle while waiting. Gas is a precious resource,'" Schachter says. The policy resulted in an immediate 3%-5% reduction in overall CO2 emissions across the entire fleet, she claims.

On Earth Day 2010, the co-op, which at the time operated a fleet of Ford Crown Victorias, bought its first Toyota Prius. The Union Cab started replacing the Fords one by one, then in 2012 took out a loan to replace its entire fleet with Priuses. The move resulted in monthly fuel savings of $38,000 across the fleet of 65 vehicles. The savings are expected to bring a return on investment in a few years. In fact, they already have surpassed the principle amount borrowed, Schachter says, which exceeded expectations.

Vancity and Ocean Spray

Then there's Vancity, Canada's largest member-owned credit union, which provides loans to local, community-oriented businesses in Vancouver. The bank – named Canada's best corporate citizen by Corporate Knights this year – also gives double-digit percentages of its profits back to the community in the form of grants, a level unheard of in corporate banking.

"We're doing all the things that traditional banks do, but we're doing it to take care of our members and our communities," says Maureen Cureton, manager of community investment.

Finally, consider Ocean Spray , the US farming cooperative best known for its cranberry and grapefruit products, which has set 2015 environmental targets, including a 15% reduction in water, a 25% reduction in consumption of non-renewable energy, a 25% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions, a 20% reduction in packaging materials and a 25% reduction in landfill waste.

In addition, the co-op has developed a set of best practice farming techniques to help its 700 member-owners operate more sustainably. It supports its member-owners to implement these practices.

Earlier this year, Ocean Spray won kudos from the Environmental Defense Fundfor cutting shipping emissions in south-east US by 20% while cutting related transportation costs by 40% (PDF) .

The challenge of definition

Defining sustainability remains a challenge even for many large, well-resourced co-ops.

The John Lewis Partnership which runs John Lewis and Waitrose retail stores in the UK uses "sustainability" to refer to everything from community engagement, local volunteering, to environmental stewardship , and employee health and well-being.

The co-operative, which defines its principal purpose as something even more abstract: the "happiness" of its employee owners, also known as partners. In March, after a strong period of growth, all 85,000 employees were awarded a bonus equal to 17% of their salaries. The partnership also maintains vacation resorts just for employees.

"There is no fixed definition of sustainability within the organisation," spokesperson Neil Spring says. "What we try to do is take a long-term view, which is a natural function of being an employee-owned business."

At its biannual conference in Cape Town in early November, the ICA presented the results of an online scan of how co-ops around the world use the term sustainability in relation to their activities. The purpose of the scan was "to understand how co-operatives are engaging in it and demonstrating it", Gould says.

As he puts it: "We can't claim we're the most sustainable form of business in the world without some evidence. Otherwise, we're going to look ridiculous."

Source: The Guardian (http://goo.gl/p25iPy)

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire